- PENNY ELLIS -

THORALBY

THROUGH TIME

Newbiggin in the Lordship of Middleham, 1100 – 1660

Newbiggin is the most recent settlement in Bishopdale, having been established in the 12th or 13th century. It is a linear village on the south side of the valley that stretches along either side of an ancient road that ran from West Burton to Kidstones Pass and thence to Buckden in Wharfedale. The section between West Burton and the east end of Newbiggin has long since degenerated into a track called Ox Pasture Lane, while the section from the west end of the village to Kidstones Pass has been out of use for so long that it has disappeared almost completely. Access to the village is now via two lanes that connect it with the main road through Bishopdale.

The photograph below shows the East End of Newbiggin. The house on the far left of the photograph is The Grange. Notice the hay pikes on the hillside behind the village. The large white building right of centre is Eastburn Cottage and Farm.

Newbiggin Mill

[This section is under construction]

Newbiggin Mill probably dates from the origin of the village in the 12th or 13th century. The earliest definite reference to it can be found in an Inquisition Post Mortem of the property of Robert de Tateshale in 1298, which included a mill, probably a corn mill, at Newbiggin worth 26s. 8d. He also owned a corn mill and a fulling mill at Thoralby, a third of a corn mill at Aysgarth and a third of a mill at Thornton Rust. It was usual for medieval corn mills to be owned by the lord of the manor, who enforced soke rights to oblige his tenants and others beholden to the manor to grind their grain at his mill. Newbiggin Mill was established on Mill Beck just above Mill Scar (see map below) in a climatic period known as the Medieval Warm Period, during which the growing of oats, rye and possibly even wheat would have taken place in Bishopdale because the climate was more favourable to arable farming than it is today.

Around 1350, the Medieval Warm Period began to give way to a colder and wetter period known to meteorologists as the Little Ice Age. This would have made it impossible to continue growing grain in marginal areas such as Newbiggin, so it is likely that Newbiggin Mill ceased grinding sometime in the late 14th or early 15th century along with several other manorial mills in the Yorkshire Dales. Newbiggin Mill, situated on Mill Beck, is probably the best preserved of these medieval mill sites.

A field survey undertaken by Stephen Moorhouse identified the sites of the fall-trough or launder, which was a wooden trough leading to the mill pond, the mill building on its millrace or leat, the miller's house, a possible drying kiln and other buildings probably used for grain storage. The leat leading to this wooden launder extracted water from the opposite side of the beck to the site of the mill pond and mill building, so a launder would have been used to carry the water over the beck to the mill pond. This type of system was quite common in medieval mills because it provided some protection to the mill from flooding. When floods occurred, the miller could remove the wooden launder to keep the flood water away from the pond and mill building or, if he left it in place, the launder, which was easily replaced, would be washed away before any significant damage was done to the mill. An abandoned track, known as a hollow way, has been identified leading from the mill to East Farm at the eastern end of the village. This would have provided a gentler access than finding a way through the crag just below the mill.

The photographs below are from an article by Stephen Moorhouse in "The Archaeology of Yorkshire, An assessment at the beginning of the 21st century", edited by T.G. Manby, Stephen Moorhouse and Patrick Ottaway.

Plate 71: Abandoned medieval water powered corn-mill on the Mill Beck at Newbiggin, Bishopdale, showing the large square stone revetting across the beck (on the left) and the leat outlet (on the right).

Plate 71: Abandoned medieval water powered corn-mill on the Mill Beck at Newbiggin, Bishopdale, showing the large square stone revetting across the beck (on the left) and the leat outlet (on the right).

Plate 73: Newbiggin medieval corn-mill, Bishopdale. Looking across the Mill Beck, with the head of the falltrough leat in the foreground and the mill pond on the other side of the beck. The long since removed falltrough would have spanned the beck, carrying the water to the pond and hence to power the mill.

1856 O.S. showing Millbeck Bridge, Mill Scar & Millbeck Spring, add site of Mill

Medieval Ridges and Furrows in Newbiggin Township

By the 13th century, the open field system of arable crop rotation was common throughout the country. Feudal lords usually owned all or most of the land in the village and the peasantry had to work without payment on the lord’s land, known as demesne land, for between two and four days a week depending on their status. In return for this they were granted strips of land rent-free in two or more open fields. These open fields can often be identified today by the ridges and furrows that separated them from one another. Examples can be seen near Thoralby, West Burton, Eshington and Croxby, but the clearest and most extensive examples are in Newbiggin Township.

Some of these open fields were very extensive: for instance, the wide expanse of ridges and furrows visible in the bottom photo were all part of Newbiggin’s East Field. The early ploughs were pulled by teams of up to eight oxen and pasture was often set aside for these valuable animals separate from the common pasture. The lane heading east out of Newbiggin is still called Ox Pasture Lane and some of the fields to which it leads are still known as Ox Pasture. The crops grown were wheat, oats, barley and rye, but oats predominated in this area because they could cope better than the other grains with our wet climate. The ploughed fields were above the flood plain, which was used as a water meadow.

Below is the 1856 O.S. Map of Newbiggin, clearly showing the Ox Pasture Lane and the fields called Ox Pasture. The lane is at the east end of Newbiggin, not far from The Grange, showing that oxen were used for ploughing.

One field was cultivated each year whilst the other lay fallow to replenish its nutrients. The lord’s demesne arable lands were usually scattered in strips in the common fields alongside those of their tenants, as shown in this diagram of a village with three fields, which I have used because I couldn’t find one with two fields. In addition to the open fields, there were meadows and pasture, including moorland grazing that was used mainly in the summer months. Meadows were divided into strips because a crop of hay was taken from them, but pastures were grazed in common.

For two thousand years and more, oxen (or bullocks) were the main beasts of burden on British farms and roads. Then, in the 40 years from 1800 to 1840, they all but disappeared - hustled into history by social reforms, industrialisation and a growing need for speed. The photograph below shows a team of 8 oxen, ploughing, courtesy of the Foxearth and District Local History Society, East Anglia.

1301 Lay Subsidy: Village Totals for the Wapentake of Hang

A tax or subsidy known as a fifteenth was levied in 1301 in the reign of Edward I and lists the tax payers for each town and village and the amount that each was required to contribute. It was called a fifteenth because the amount payable was a notional fifteenth of the value of one’s moveable goods.

There were no taxpayers in Newbiggin.

Bishopdale Chase, Newbiggin and the Forest of Wensleydale

This map below was produced by John Speed in 1610 and clearly shows what is called ‘Busshopsdale Chase’. The sale by King Charles I of the Lordship of Middleham to the City of London in 1628 gives an indication of the extent of Bishopdale Chase at that time. Specific exclusions from that sale included “all liberties and jurisdiction of chases as far as our chase of Bishopsdale extends in the towns of Walden, Thoralby, Newbigging, Aikesgarth and Bishopsdale.” So it comprised all of Bishopdale and Walden together with Aysgarth, the area I have shaded in red on the map. To the west, it bordered on the royal Forest of Bainbridge, which I have coloured green, while immediately to the south was Langstrothdale Chase, coloured blue, which also belonged to the Crown.

Hunting forests and chases were not thick forests but a mixture of woodland and open country. They also included arable land, pasture and villages, either because these existed before the chase was established, as in the cases of Thoralby and West Burton, or because the king had granted special permission for a limited amount of forest to be cleared, as may have happened at Newbiggin. Among the game that was protected for the king to hunt were deer, wild boar (which were hunted to extinction in England in the 13th century), wolves (which became extinct in England in the early 16th century, the dales being one of their last refuges), hares, rabbits and game birds. Two 16th century writers mentioned that Bishopdale Chase was famous for the size of its red deer.

The Foresters of Bishopdale Chase, Newbiggin and the Carr

Foresters maintained and protected the forests and chases. As late as 1621, laws against hunting were still being enforced in Bishopdale: among those arraigned before the quarter sessions in Richmond that year were “A butcher of Niwbegin in Aiskarth, and two labrs of the same for breaking the King’s Park &c at Bushopdale, called Bishopdale Chase, and there shooting a doe younge with fawne with an arrow shot out of a crossbow”.

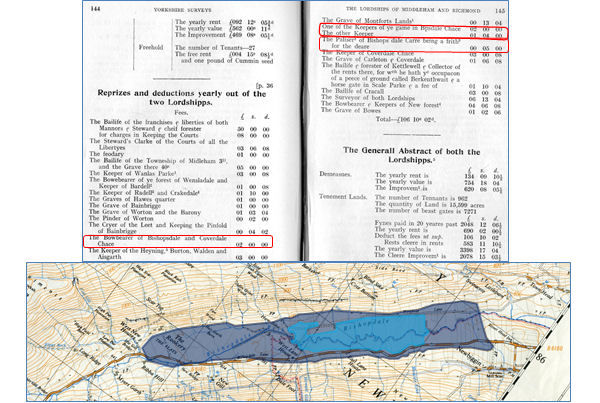

A survey of the lordship of Middleham undertaken in 1605 recorded that the Bowbearer of Bishopdale and Coverdale Chase, the title by which the head forester was known, received an annual salary of £2 and that other employees of the lordship of Middleham included two other “keepers of ye game in Bishopsdale Chace” plus a “Paliser of Bishops dale Carre being a frith for the deare”. A frith was a protected deer park and a palliser was someone responsible for maintaining the fences of a deer park.

Seventy years earlier, in the 1530s, John Leland had referred to a “pretty carr or pool” in Bishopdale. The word ‘carr’ means swamp in Old Norse, so it seems that vestiges of the post-glacial lake in Bishopdale survived until the seventeenth century.

The Carr originally stretched from below Hargarth Farm at the west end of Newbiggin to where Ribba Hall now stands (the area shaded dark blue, below), although by the 16th century, it had shrunk to the area shaded light blue with embankments at each end, parts of which are still visible. It was probably drained following the sale of Bishopdale Chase by Charles II in 1661.

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

Although Bishopdale was a rural backwater, it wasn’t entirely immune from momentous national events. When James IV of Scotland was killed at the battle of Flodden Field in Northumberland in 1513, the 500th anniversary of which was commemorated this year, men from Wensleydale and Bishopdale fought in the English army. A ballad written fifty years later by Richard Jackson, a schoolmaster from Ingleton, refers to Lord Henry Scrope of Castle Bolton leading into battle a contingent of dalesmen. “With him did wend all Wensleydale…from Bishopdale went bowmen bold.”

A Survey of the Lordships of Middleham and Richmond, 1605

A Survey of the Lordships of Middleham and Richmond in 1605 stated that ‘Bishops dale Chace’ in the lordship of Middleham consisted of six parts: Burton, Walden, Thorolby, Bishopsdale, Newbigging and Aisgarthe. It named all the tenants in each of these townships, and listed how many houses there were, how many outhouses (most of which would have been barns), how much meadow, arable and pasture and how many pasture gates or beast gates there were on the open pasture.

The information is summarised in this table, which includes the annual rent paid to the king and the annual value. The numbers of tenants and houses show clearly that in the early 17th century Thoralby had twice as many tenants and almost twice as many houses as any other settlement in and around Bishopdale, although the figures for Aysgarth should be ignored because only part of the township was in Bishopdale Chase.

In the whole of the lordship, Thoralby was second in size and value to Middleham itself. Perhaps the most significant figure is the amount of arable land, a total of 339¼ acres in Bishopdale Chase as a whole, which reflects the need for rural communities to be largely self-sufficient at that time. Most of the crops would have been oats, used to make haverbread and oatcakes, which formed the main element of the staple diet of dales folk at that time, but some vegetables would also have been grown to add variety to the diet.

Below is the table of names of Newbigging Tenants in 1605. The only surname still in the village today is Wilkinson.

Below are Totals of the table above.

Cleare Improvemt.

Some Observacons concerning these two Lordshipps

Although the Lordship of Middleham was sold by Charles I to the City of London in 1628 to pay off some of his debts, there were several exclusions from the sale, including Bishopdale Chase, although the lordship of Thoralby was included in the sale. A further document entitled “Some Observations concerning these two Lordships” (the lordships of Middleham and Richmond), written sometime after 1628, provides some interesting glimpses of Bishopdale in the 17th Century. It states: “There are few or no woods or tymber trees in the two Lordshipps besides the woods growing in Radale, Bishops dale Chace & the Heaning.” This reminds us that the Forest of Wensleydale and Bishopdale Chase were not heavily wooded.

Another statement it made was: “The greatest part of these two Lordshipps consists of Medow and Pasture, ℓ Out Common, wth a small quantity of Arrable land, it being not able to beare Corne for ye coldness of the soyle and the length of winter there.” Fairly self-explanatory, but ‘corn’ in this sense means wheat. As I have already mentioned, oats, vegetables and probably a little barley were grown.

This statement reminds us that, until the end of Elizabeth’s reign, people everywhere in the north, including those in Bishopdale, were expected to provide military service to protect against marauding raids from Scotland. “That so often as occasion should require they should be ready to attend the Lord Wardens of the Marches against Scotland with horse ℓ men well furnished for warre at theyre owne charge as long as need should require…But this service ceased at the coming in of King James.” It will have been this requirement that led to the men of Bishopdale being involved in the Battle of Flodden Field, mentioned above.

It seems that enclosures had begun by this time because the document states: “The enclosures are most of them rich grounds ℓ lye all in the dales encompast wth mounteynes, moores and fells.” It is likely that the principal enclosures were near the village in the lordship of Thoralby, which the City of London sold in 1661 to a Major Norton, who lived near Richmond. Enclosures probably had more impact on how the dale looked and on how its economy developed than any other event since the Anglo-Danish settlements.